The feminisation of agriculture refers to the increasing participation of women in agricultural activities. But how can this shift translate into greater decision-making power and economic independence for them?

Women contribute around 63 per cent of the agricultural labour force in India, yet they lack access to key resources such as land ownership, finance, and advanced farming technologies. In this context, what does the feminisation of agriculture imply? Does this growing participation of women in agriculture – often driven by male outmigration – signify empowerment or does it reinforce gender disparity in land rights and decision-making power?

What does the female workforce participation rate say?

The female workforce participation rate in India reached its peak at 40.8 % in 2004-05 but has declined since. However, since 2017, the female labour force participation rate (FLPR) has seen a rising trend after years of decline. This increase has been more pronounced in the post-Covid years. The rural FLPR increased from 41.5% in 2022-23 to 47.6% in 2023-24, while the urban FLPR increased from 25.4% to 28% over the same time period.

This growth in FLPR could be attributed to the economic recovery following the easing of lockdown restrictions, which prompted many women who were previously not part of the labour force to seek employment. In addition, the sudden rise in FLPR in the last few years has also been linked to economic distress, which has forced more women to look for alternative income sources.

The feminisation of the Indian labour force, or the increase in the number of women participating in paid work, however, requires a deeper examination. The rise in FLPR is largely driven by the rise in self-employment among women, especially in agriculture. Analysis of state-wise census data indicates that in states where women’s workforce participation has increased, it has been primarily driven by the increase in women’s role in agriculture.

This trend highlights the lack of non-farm job opportunities for women, with most employment opportunities for rural women remaining confined to agriculture. This leads to feminisation of agriculture.

How do we define feminisation of agriculture?

Economic literature interprets feminisation of agriculture in two ways. First, it refers to an increase in the proportion of farm related work undertaken by women, including their growing responsibilities as smallholder cultivators or casual agricultural wage workers.

Second, feminisation of agriculture can also imply an understanding of women’s control, ownership, and participation in agricultural resources and social processes. This includes women’s ownership of farmland, land rights, and decision-making power over crop selection and input usage, such as fertilizer application.

Several factors contribute to the feminisation of agriculture. The structural transformation of the Indian economy has led to a declining share of agriculture in GDP, with a shift from agriculture to the service sector. Additionally, rural distress has forced men to seek livelihood opportunities outside agriculture, often migrating to non-farm sectors.

A number of other factors such as declining agricultural production and productivity, increasing cost of agricultural inputs, higher risks of crop damage due to climate change, limited employment opportunities, and the growing aspirations of newly literate youth in rural areas have further fueled male migration out of rural areas. As a result, women who are left behind take on multiple responsibilities, particularly in farm work.

Gender disparity in land ownership

The National Commission on Farmers’ 2005 report found that an increasing number of women are undertaking agricultural tasks such as taking care of the land and working as helpers. It is estimated that women undertake around 80% of India’s farm work and make up over 42% of the agricultural workforce. According to PLFS 2023-24 data, over three-quarters (76.95) of rural women are engaged in agriculture.

Despite their significant contribution, female farmers remain largely invisible. The Agriculture Census of 2015-16 reported that while 73% of rural women workers are engaged in agriculture, only about 11.72% of the total operated area in the country is managed by female operational holders. This reflects the gender disparity in land ownership and control. Additionally, women’s landholdings are predominantly small and marginal, which can be attributed to longstanding patterns of unequal land distribution.

In India, women can acquire land through inheritance, gift, purchase, or government transfers. However, these systems are often skewed against their equal participation. For instance, women are more likely to be financially constrained than men to purchase land, making inheritance one of their major means of land ownership. Yet, social biases and norms make it difficult for women to inherit and control land.

The 2017 Uttar Pradesh land distribution programme can be highlighted here. Land titles were distributed to 331 landless households in two villages in Mirzapur district of the state – Sirsi and Karkad. 80 land titles were distributed in Sirsi, including eight to single women, and 251 land titles were distributed in Karkad, including 16 to single women. This means only 7% of the land titles went to single women. Studies have also underlined that land rights play an important role in women’s economic security and decision-making power.

Towards gender equity in agriculture

It has often been stated that women’s participation in paid work should not be confused with their empowerment. Women often face a “double burden of work” where they are forced to maintain a balance between paid employment and unpaid household and caregiving responsibilities. Similarly, women’s involvement in agriculture does not necessarily equate to empowerment.

The agrarian economy in India has been going through distress with a fall in agricultural incomes. Hence, women’s engagement in agriculture as cultivators may not be economically empowering, especially in the absence of viable non-farm employment opportunities. Moreover, research has also found that women usually lack significant decision-making powers in relation to use of fertilizers, household assets, alternative livelihood options, etc.

The feminisation of agriculture is often discussed alongside the feminisation of poverty or feminisation of agrarian distress. As male members of the family migrate in search of better opportunities, the women left behind are forced to move into agriculture – often seen as a less advantageous livelihood option.

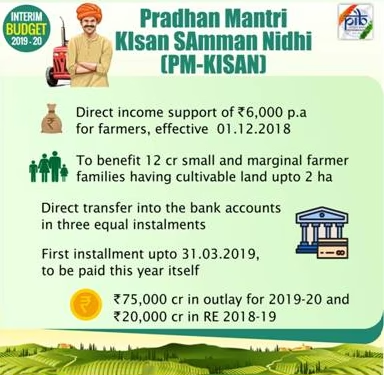

Furthermore, unequal land distribution and the lack of land ownership among female farmers make it difficult for them to access credit and other financial resources. This, in turn, limits their eligibility for some government schemes and benefits. Studies have also found that women are less likely to avail loans under schemes like the Kisan Credit Card and receive assistance from schemes like the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi Yojana.

In addition, the image of a farmer has always been associated with men. Unless this perception changes, female farmers will continue to be overlooked. Agriculture is not just about sowing and harvesting – it is also about investing in land and critical decision-making. Therefore, measures like placing women at the core of policies around agriculture, equal distribution of land, equal access to mechanization, and gender-responsive climate mitigation policies would help in achieving gender equity in agriculture and empower women.

Mains Practice Questions

Q1) How does the increase in farm-related work undertaken by women contribute to the feminisation of agriculture?

Q2) In what ways does feminisation of agriculture relate to women’s control, ownership, and participation in agricultural resources?

Q3) Why is women’s ownership of farmland and decision-making power over agricultural resources crucial for their empowerment?